“Waiting for Other” by Nooroa Tapuni

Title:

Artist(s) and People Involved:

Exhibiting Artist(s):

Symposium:

Venue(s):

Medium:

Artist Statement:

The indigenous cultures of the Pacific believe material and immaterial worlds are connected, wherein the present exists, our past and future. Centred in this multi-layered and multidimensional understanding of the world, genealogy (akapapa, whakapapa) manifests interconnection and continuity through inherent recursive strategies.

Through the lens of genearchelogy (Refiti, 2008), the manifestation of our ancestor is made present through the body. Here the notion of self (I) in the singular is positioned in relation to self as other as in ancestor as in the multiple. That is to say, the notion of self is understood as the binding relation of one’s ancestors through one’s gene archaeological matter, manifesting the past in the present.

It is through this understanding of self that the thematic consideration for this work begins. The project explores the extent interconnection and continuity, from an indigenous Pacific lens, can be explored through digital means.

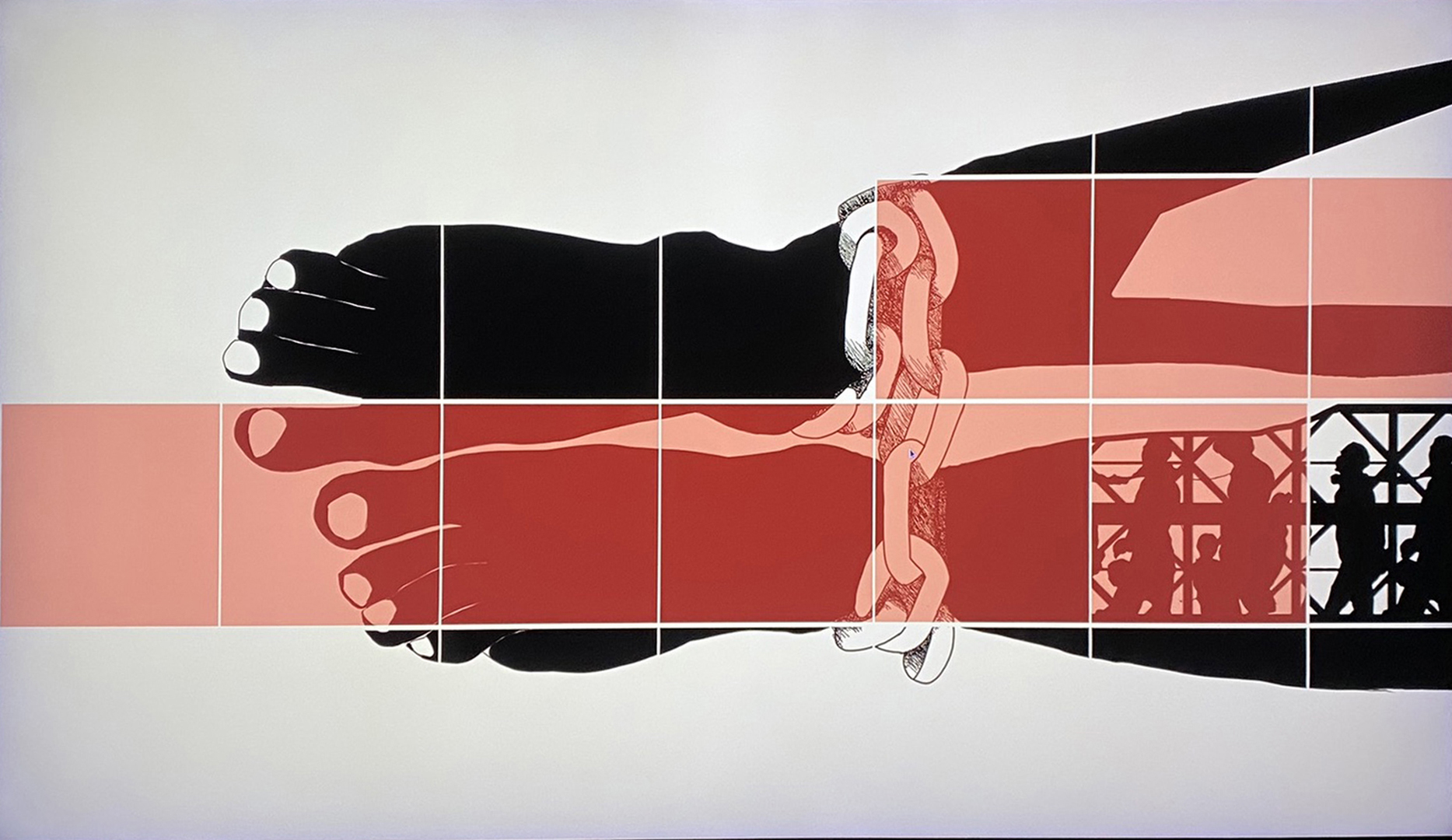

The project has a two-forked approach. The first sequences body parts in relation to indigenous pacific cosmological beginnings. The animated sequence of body parts is a reorientation of ‘self’ and ancestor. The second looks at the relation between the skin of the body and skin of the digital image. Crucial to this exploration is the notion of tu ke (to stand in difference),as in the negative stereotype applied to black skin, and te’ta’i, (to stand as an(other) as in ancestor). This two-fold approach calls into question what ancestors manifest through the skin of the body and the skin of the digital image, and to what the digital interface surfaces in us.

Reference:

Refiti, A. L. (2008). The forked centre: duality & privacy in polynesian spaces & architecture. Alternative: An International Journal Of Indigenous Scholarship, 4(1), 97 – 106.

Additional Images:

- ISEA2022: Tapuni_waiting for other (working title)

- ISEA2022: Tapuni_waiting for other (working title)