Naeem Mohaiemen: Otondro Prohori, Guarding Who

Title:

- Otondro Prohori, Guarding Who

Artist(s) and People Involved:

Exhibiting Artist(s):

Symposium:

- ISEA2010: 16th International Symposium on Electronic Art

-

More artworks from ISEA2010:

Venue(s):

Creation Year:

- 2009–2010

Artist Statement:

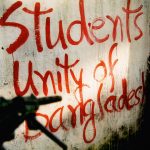

The images in Mohaiemen’s slides show re-stagings of the interstices between political life, surveillance, and the media, in a globalized world. They display a skewed glance at reality from the perspective of shadow puppet theater. Military camps, building demolitions, wall slogans, demonstrations, and personal details merge into a narrative about the foundations of distrust in digital culture.

Naeem: The Otondro project emerges from a political praxis that takes the media – mass and individual – as key players in the political struggle. Do you see this setting as specific for Bangladesh, or is it a more general condition that the work responds to?

I’ll wait to have an audience walk into portions of this project and see what they draw out of it. The universal will come out with a little bit of serendipity, I’d rather not force-feed or produce a summary. Otondro of course came out of a specific context, the military government that ran Bangladesh for two years (2007-2008), and the ensuing meltdown in our lives over that period. It was a repetition of a pattern Asia had seen many times before (the benevolent strongman, we will only be here for few years, for the greater good, we had no choice, we did not want this but were compelled…). It also echoed strands that appear in mutated forms in many familiar contexts: country, nationalism, histories, borders and unintentional comedy.

The work deals with the ‘embedded’ status of all our mediated communication. Is it more important for you to give a ‘precise’ poetic description of the condition that this addresses?

Actually the work is often taken to be precise because there’s so much text in my work, which seems to trigger the idea of factual descriptions or journalism. But because the specific histories I re- search are not excavated, even when there is an amount of whimsy or invention, it’s not clearly grasped. People don’t know which portions of the narrative are fiction, and that makes things slip out of reach.

Do you have alternative media usages in mind when you think about the everyday praxis that you portray? Do you imagine an alternative media ecology?

Well I think the continuous migration of clashing practices into the visual arts over the last decade has already created one such media ecology. If you look at an instance like Raqs Media Collective’s co-curation of the last Manifesta Biennial, there’s a collision of many different disciplines and forms, in a fairly energetic way, that creates space for my peer group.

In this context, what is it, for you, that people can trust?

Family and friends. The novel as a form that will outlast gimmicks. MRI scans (sometimes). Glass bottles for water. The last thought before going to bed.

Naeem Mohaiemen

Back to elections. Back to democracy. The new normal. Mission accomplished.

But the residues are still here. A temporary camp for highway construction. Phantom investor. New chairman. List of approved guests. Shadow falls.

A theorist talks about the architecture of occupation, hollow land. But security presence in Asia is subtle. Suit tie coat bideshi degree. Think tanks, seminars, conferences, talk shows, newspapers. Everyone has an opinion on the century’s obsession. War against an invisible enemy.

They tell us, we know all the answers. How to catch them, inside and outside borders. How to keep them out. Facial hair, surname, skin hue, city of birth, passport – the full spectrum domination of motivation recognition. It’s not who you are, it’s who we say you are.

Dhaka is now inside a security zone bubble. Will democracy re- move the steel wire barricades and midnight checks on Dhanmondi Bridge? On the day after the state of emergency was lifted, I saw a homeless woman drying her family clothes on that same wire barricade. A sweet, fleeting moment. But a few days later, the barricades were back in action. The demand for ID, the sudden stop and search, the rummaging inside your camera bag, the interrogation. Eto raat e beriyechen keno? Janen na din-kal kharap?

I feel a searing nostalgia for open space, a time before these ‘temporary’ structures. Temporary camps that never leave. It’s all to make you safe and secure. Safe from what? A long pause.

Yourself, your weaker side, your politics, your affiliations, your night- mares, your ideology, your rights, your friends and neighbors.

Your dreams.

October 2006

Dhaka is ripped open by ferocious street battles between the two main political parties, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the Awami League (AL). At issue is whether the ruling BNP will allow fair elections.

November 2006

Grameen Bank’s Muhammad Yunus arrives in Oslo to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. He is the third Bengali to win a Nobel, after Rabindranath Tagore in 1913 and Amartya Sen in 1998, but the first from Bangladesh (the other two laureates are technically ‘Indian’).

January 2007

United Nations representatives send a letter stating that if the Bangladesh Army supervises any ‘controversial’ elections under the BNP government, they could lose UN peacekeeping quotas. Bangladesh is the largest supplier of soldiers to UN blue-hats.

On January 11th (1/11), the Army declares a state of emergency, removes the civilian administration and forms a ‘Caretaker Government’. It is Bangladesh’s third military government after1975 and 1982.

February 2007

Among the army’s new austerity measures is the requirement to have all lights out by 8 pm to save electricity. Officials arrive at the Public Library to eject people and enforce the new law.

Muhammad Yunus announces he will form a ‘third platform’ and run for President. He is seen as tainted by association with the military government and meets a boycott on university campuses.

April 2007

As Yunus continues to travel all over the world for post-Nobel events, he is described as ‘out of touch’ by local media. Seemingly rejected by the intelligentsia as well, he abandons his political bid.

May 2007

CNN stringer Tasneem Khalil is picked up by military intelligence for writing against the army. His wife fears he is being tortured and an international appeal is launched.

Two days after his arrest, Tasneem is released. He goes into hiding while his newspaper editor negotiates to have his pass- port returned.

Interrogators selectively leak contents of Tasneem’s computer and allege that he is funded by anti-army politicians. Jonotar Chokh (‘Eyes of the People’) publishes cover story ‘Laptop Conspiracy to Overthrow Government’.

June 2007

Tasneem’s passport is returned. He flees into exile in Sweden and has never returned to Bangladesh since.

July 2007

Caretaker Government escalates arrest campaign against politicians, culminating in the midnight arrest of AL leader Sheikh Hasina. Her rival, Khaleda Zia of the BNP, remains outside jail.

August 2007

A confrontation between soldiers and university students, at a football match, escalates into rioting that spreads across the country.

After days of student riots, the army backs down and vacates the campus. It is a costly loss for the regime and the beginning of the end for the Caretaker Government.

September 2007

Khaleda Zia is arrested, along with her sons who are considered the kingpins of Bangladesh politics. The move is seen as bring- ing parity of arrests, as leaders of both parties are now in jail.

December 2007

The army bulldozer campaign against illegal buildings hits a major snag with the infamous Rangs Building. After a floor collapses, bodies of demolition workers killed in the accident are trapped in rubble for almost a week. As bodies decompose, the press talks ‘omens’.

January 2008

Although the Caretaker Government began with a ‘war on corruption,’ rumors become popular that the money trail is reaching army officers as well. Civilian gossip encompasses institutions like Trust Filling, the army-welfare-trust run gas station.

June 2008

Military regime releases Sheikh Hasina after sustained inter- national campaign. Part of the media debate leading up to her release is whether she is suffering slow poisoning from prison food.

August 2008

The medical community is in turmoil as the MRI scan of Khaleda’s son Tarique Zia becomes a key exhibit in a war of words. At issue is whether the scan shows he was tortured in custody, or that he had an old spinal injury.

September 2008

Military regime releases Khaleda Zia, and her two sons are allowed to leave the country. Negotiations begin to return power to elected officials, which includes implicit assurance that there will be no trials of military officers.

December 2008

Sheikh Hasina’s Awami League wins a landslide victory in Army-supervised elections. The rightist BNP and the Islamist Jamaat e Islami are reduced to a small minority in Parliament.

February 2009

The new government faces its’ biggest crisis when a mutiny erupts at the headquarters of the border guards, Bangladesh Rifles (BDR). While negotiators meet with mutiny leaders, behind the scenes the rebels hunt down and kill their senior army officers inside the barricaded headquarters.

The final grisly death toll from the BDR massacre is 81, almost all senior army officers. A national debate erupts over whether the Army should have been allowed to capture the headquarters by force.

Army officers, reeling with grief, have an angry exchange with Prime Minister Hasina during a closed-door meeting, clandestine recordings of which are leaked. The government temporarily bans YouTube to prevent the tapes from circulating.

April 2010

Interrogation of arrested BDR soldiers yield no conclusive evidence of a ‘foreign link’. 56 rebels die while in custody, but they are classified as ‘heart attack’.

May 2010

After a year of allegations of foreign conspiracy, the government seems to conclude that the BDR rebellion was over basic grievances of salary, ration and promotion. However, investigators are still mystified by the brutal killing spree.

July 2010

After legal debates over whether the mutineers would be tried in civil or military court, the government finally brings charges against 824 soldiers. Death sentences are expected.

In an attempt to remove the stigma of the rebellion, the border guards get a new name and uniform. No word yet on whether their slogan will change. It is currently ‘Otondro Prohori’–never sleeping, always on guard.

Full text (PDF) p. 76-79

Contributors:

Sound: Kaffe Matthews