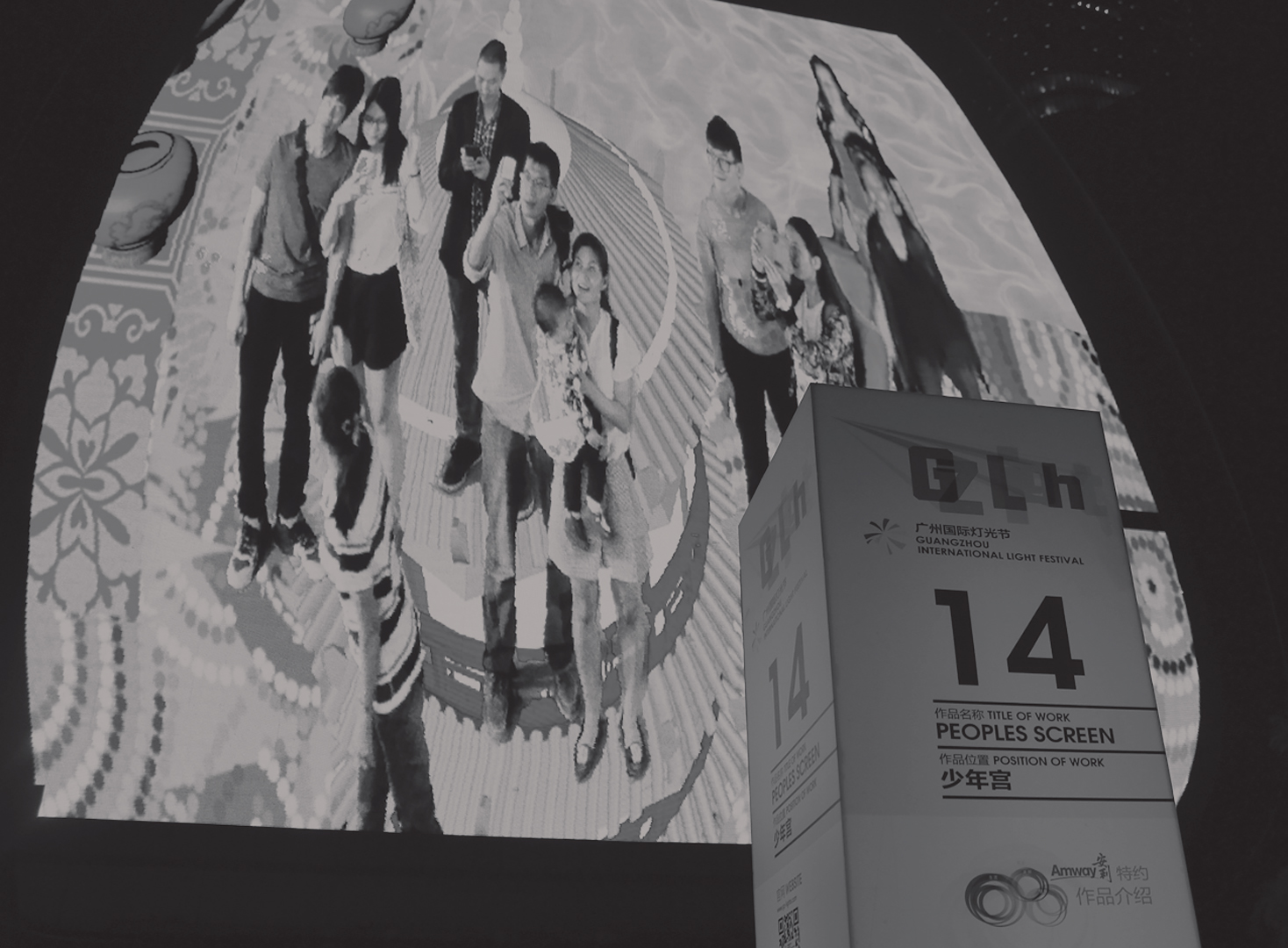

“Peoples Screen” by Charlotte Gould, Paul Sermon

Title:

Artist(s) and People Involved:

Exhibiting Artist(s):

-

Charlotte Gould

-

- University of Brighton

-

Paul Sermon

-

- University of Brighton

Symposium:

Artist Statement:

“Peoples Screen”. In November 2015 Public Art Lab Berlin commissioned a new version of “Occupy the Screen” for the Guangzhou Light Festival in China. Sharing the same time zone, the installation was connected for 12 evenings with the Northbridge Piazza public video screen in Perth, Australia and was extensively reworked to converge scenes from the cities of Guangzhou and Perth. Renamed “Peoples Screen”, the installation was hugely popular, involving over 25,000 participants in Guangzhou alone. For the fist time the citizens in Guangzhou, China and in Perth, Australia were brought into exchange through an artistic real time performance on public screens from the 15th to 29th November 2015. “Peoples Screen” was presented during the Guangzhou International Light Festival on the screen at the Flower Garden Square and on the Northbridge Screen in Perth, offering public audiences the opportunity to co-create coincidental encounters and spontaneous interactions between these two cities. This installation builds on practice-based research and developments of previous interactive works for large format urban screens including “Occupy the Screen” for “Connecting Cities Urban Reflections” in September 2014 between Supermarket Gallery Berlin, Germany and Riga European Capital of Culture, Latvia.

This new installation pushed the playful, social and public engagement aspects of the work into new cultural and political realms in an attempt to ‘reclaim the urban screens’ through developments in ludic interaction and internet based high-definition videoconferencing. By making use of illustrated references to site-specific landmarks in Guangzhou and Perth, audiences were invited to occupy the screen. The concept development of “Peoples Screen” was inspired in part by 3D street art as a DIY tradition, referencing the subversive language of graffiti. The interface borrows from the ‘topoi’ of the computer game, as a means to navigate the environment; once within the frame the audience becomes a character immersed within the environment. “Peoples Screen” linked two geographically distant audiences using a telematics technique; the installation takes live oblique camera shots from above the screen of each of these two audience groups, located on a large 8 x 8 metre green groundsheet and combines them on screen in a single composited image. As the merged audiences start to explore this collaborative, shared ludic interface, they discover the ground beneath them (as it appears on screen as a digital backdrop) locates them in a variety of surprising and intriguing anamorphic environments, where from a particular position the characters can look as if in precarious situations. In “Peoples Screen” this included suspended on a planplank high above a lake, or on an over sized wooden bridge. The installation was designed for the audience to engage in an intuitive way and there was no preconceived ending. The position of the urban screen as street furniture is ideally suited to engage with people going about their everyday life, and often the most interesting outcomes are discovered through the ways that the public interprets and re-appropriates this environment. The interaction is an open system aiming to offer the audience a means of agency to be creative and make individual decisions. The area of play was clearly demarked as a space via the green screen groundsheet in both Guangzhou and Perth, identifying a theatre of play once in the space the participant engages as they wish. The environment may suggest activities or events but the audience are free to respond as they choose, which is key to the characteristics of an open system, that there is much opportunity for the unexpected and that chance encounters can change the direction of a narrative that is unfolding.

We used our experience of previous installations to inform elements of the design to include objects that people can engage with, but also playing with perception and illusion. This included a Pop Art inspired tunnel, which participants intuitively jumped into, and steps, which disappear into an underground bunker. From our observations optical illusions acted as a signifier of play, people inherently recognized the environment as playful and inviting. We also used the notion of the computer game as a design reference, incorporating box hedges suspended in space, which participants recognized as a game platform to jump on and between. The environments often implied a physical response such as jumping, diving or climbing, including a swimming pool to dive into, coloured boxes to climb across and a bridge to jump off. This contributed to the active approach that the majority of the participants took.

In both “Peoples Screen” and “Occupy the Screen” people of all ages took part and adults were as likely as children to engage. We observed an uninhibited willingness to play from children. One girl played for hours engaging with the set, pretending to sit at the table, jumping into the tunnel, walking the plank etc. She engaged in a very performative way, with confidence and exaggerated movements. We also observed this enhanced ability to perform in adults as well as responding to the environments they tended to engage with others, pretending to scratch someone’s head, or hold hands in order to jump into the tunnel together, or lift someone up from the pool. The remoteness of the installations appeared to give confidence to cross into personal space that might otherwise be seen as a physical invasion of space. In many ways “Peoples Screen” broke down cultural and social barriers, both in the local communities, but also between two cities, where new collocated spaces and creative encounters could be founded and occupied.

Through this research project, we have developed a framework for open participatory artworks for urban screens to maximize audience agency through play, engaging the public in new ways in the urban environment, offering the public agency and developing events that create community memory. Levels of openness were measured, from which we were able to define key characteristics, to provide a framework for open interactive systems for urban screens. “Peoples Screen” aimed to include the widest range of urban participation possible and aligns to a ‘Fluxus Happening’ in a move away from the object as artwork towards the street environment and the ‘every day’ experience. It also borrows from a tradition of early 20th century media developments where audiences were transfixed by the magic of being transported to alternative realities though early films at the traveling fairs. Lumière contemporaries, Mitchell and Kenyon, whose films of public crowds in the 1900’s present a striking similarity to the way audiences react and respond to “Peoples Screen”. These pioneering fairground screenings of audiences filmed earlier the same day possess all the traits of live telepresent interaction, albeit through the latency in processing, whereby the audience play directly to the camera and occupy this new public space by performing to themselves and others when screened later.